My mother became almost hysterical. “Don’t get too close,” she screamed.

I didn’t. I laid down and crawled forward until my head poked over the edge. I could see down almost a mile into the canyon. It was an experience I’ll never forget.

Of course, I had no intention of going over the precipice. Although if I had crawled forward only a few more inches, gravity would have ensured that I did.

This incident came to mind years later when I began my study of economics and investments. I became convinced that the global economy was approaching a precipice that could lead to a worldwide financial collapse. The cause of this chaotic unwinding would be excessive debt combined with leveraged bets financed by more debt.For many years, I believed that if individuals, companies, and governments stopped borrowing so much money, our world could avoid this chaotic unwinding. But I now think it’s inevitable.The global economy floats on a gargantuan mountain of debt, collateralized, re-collateralized, hypothecated, and semi-hypothecated debt. Total world indebtedness at the end of 2016 came to $217 trillion. That’s roughly 325% of global GDP.

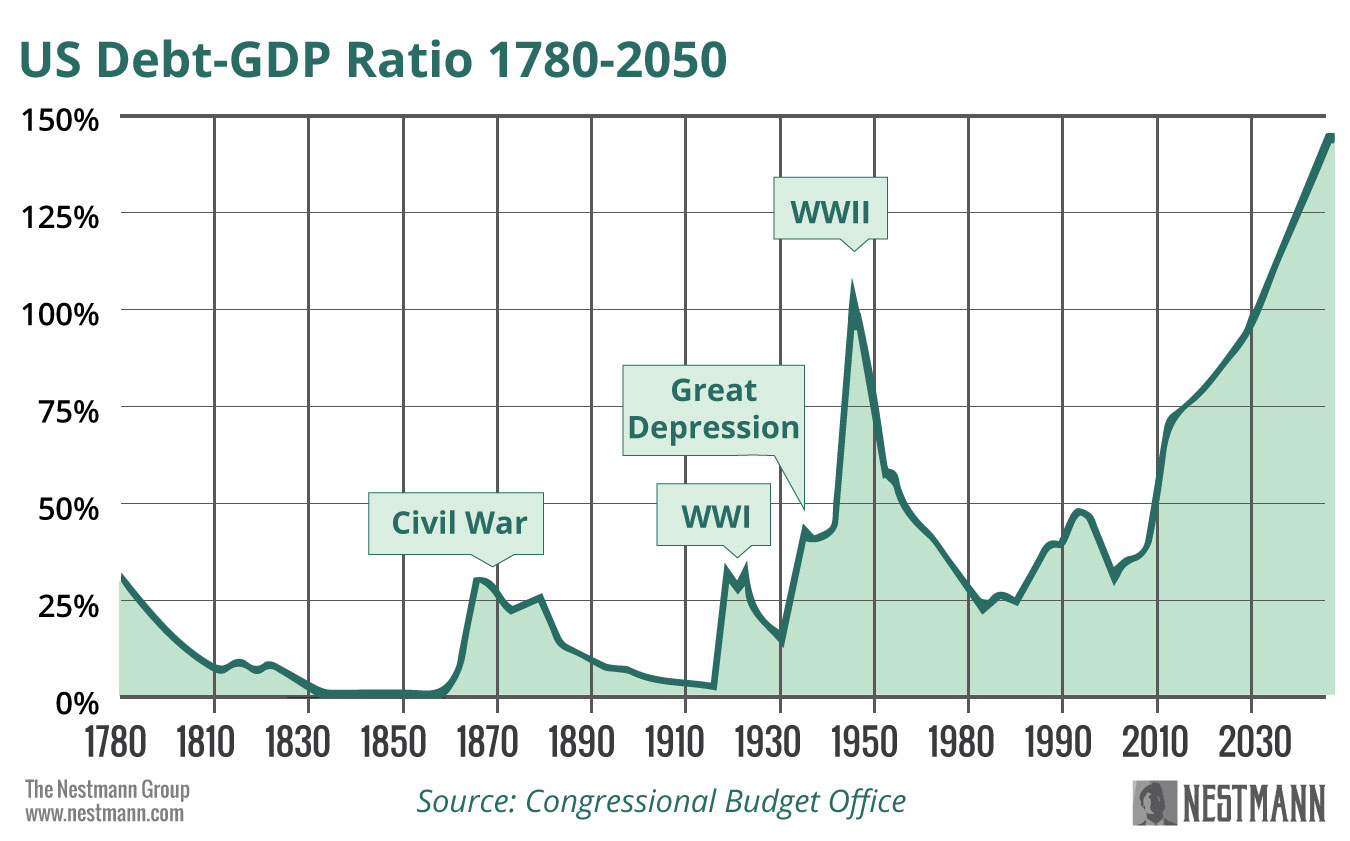

In the US, our federal debt-to-GDP ratio is only 106%. But that’s still the highest ratio since World War II.

And it’s set to go higher – much higher. Here’s a chart released in 2017 by the Congressional Budget Office. It shows debt levels rising steadily until 2050.

It is now mathematically impossible for the US government to ever pay off its debt of nearly $20 trillion. For the 2016 fiscal year, the federal deficit was $587 billion. But the gross federal debt increased by $1.4 trillion, thanks to “off-budget” items that aren’t included in the official total.

Even if the feds dramatically reduced discretionary spending by slashing defense spending and abolishing useless agencies such as the Department of Education, they wouldn’t come close to balancing the budget. That’s because spending on entitlements such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, etc. is accelerating. The cost of these benefits now amounts to more than 40% of federal spending. Based on projections from the Congressional Budget Office, the total cost for these programs in 2017 will be about $83 billion greater than 2016. In 2018, the cost will grow by another $170 billion compared to 2016, and in 2019, an increase of $335 billion.

And that’s just for starters. Federal agency debt isn’t included in the deficit numbers. It comes to an additional $8.6 trillion, and increases by several hundred billion dollars each year.

The only one way out is for the government to default on these obligations. And when that happens, the results won’t be pretty.

American households and businesses are up to their eyeballs in debt as well. At the end of 2016, the private debt-to-GDP ratio came to 150%.

On top of all this debt, we have an ocean of traded derivatives – bets on the value of a stock, a bond, an interest rate, etc. As of June 2016, the notional value (i.e., the value of an underlying asset at its spot price) of these derivatives came to an eye-popping $544 trillion. That’s more than 600% larger than the entire global economy.

At its heart, the economic crisis of 2007-2008 didn’t occur because people made stupid investment (and especially borrowing) decisions. They did, but the crisis was mainly caused by the collapse of the derivatives market. The collapse of Bear Stearns in 2008, for instance, came about because the hedge funds it operated were stuffed full of collateralized debt obligations consisting primarily of bets on high-risk mortgages. Credit default swaps wiped out insurance giant AIG, until US taxpayers ponied up for a $180 billion bailout.

Could it happen again? Of course. That’s why governments worldwide are pulling out all the stops to prop up global markets. Japan’s central bank, the Bank of Japan, now owns an astonishing 60% of the nation’s entire Exchange Traded Funds (ETF) market. When the Chinese stock market swooned in 2015, the government blatantly manipulated it. Securities regulators suspended trading of about 50% of listed securities – more than 1,400 in all. The Chinese central bank even gave money to brokers to make it easier for investors to buy with borrowed money. As central banks do, it created the cash out of thin air.

I don’t see how this can possibly end well. It takes us much further down the road to what economist John Maynard Keynes called a “liquidity trap.” It essentially means that central banks have run out of options to stimulate the economy.

To avoid a liquidity trap, central banks have been urged by the International Monetary Fund to engage in “financial repression” (yes, that’s the exact phrase). Tools for this purpose include bail-ins, higher inflation, interest rate caps, capital controls, and more. The IMF even proposes a “one-off capital levy” – outright confiscation – of 10% or more of private savings. If you live in a cradle-to-grave welfare state, this could soon be the new reality.

But financial repression works only as long its targets – individuals, families, and businesses that have built up capital over years or decades – don’t catch on. And here governments have a big problem. They no longer have the trust of their wealthiest and most productive citizens. That’s a big reason over $20 trillion in private wealth now resides outside the countries where it was generated.

Increasingly, a big chunk of this wealth is being invested in physical assets, not financial assets that can be bailed in, levied upon, hypothecated, or hyper-hypothecated. That’s one reason a painting by impressionist artist Paul Gauguin sold for nearly $300 million in a private sale in 2015.

It’s not just art, by the way. Prices for classic cars, rare wines, numismatic coins, and other collectibles are all soaring. A 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO sold at auction for an astonishing $38.1 million in 2014. But personally, I prefer more traditional stores of wealth like gold, silver, and real estate owned without a mortgage.

If you can hold these assets outside the country you live in, and (in the case of precious metals) in a private vault (not a bank), so much the better. You’ll be more prepared for the next chaotic unwinding than most other people. And since you actually own these assets rather than being an unsecured creditor for assets you hold in a bank, you’ll never be bailed in.

Reprinted with permission from Nestmann.com.