“I am today ordering a freeze on all prices and wages throughout the United States.”

After a short transition period, any increases in wages or prices would need to be first approved by the government.

What would happen next? We don’t have to look very far to see the consequences of such actions. That’s because on August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon made that exact announcement.

The results were disastrous. Farmers stopped shipping out their crops for processing. Manufacturers laid off workers and cut output. Food shortages quickly developed.

When Nixon stated this declaration, I was a teenager. While my mother initially thought price controls were a wonderful idea, she changed her mind only a few weeks later. She found out that she could no longer buy her favorite brands in stores. Manufacturers realized they could not make a profit by delivering them at a government-controlled price.

Of course, there are many modern analogies. For instance, Venezuela has had stringent price controls in effect for over a decade. Not surprisingly, supermarket shelves have been empty for years. There are pervasive shortages of food, medicine, and other necessities.

Most of us almost instinctively recognize the folly of wage and price controls. Yet, we’re perfectly content to have the government control the nation’s monetary system. This occurs through the Federal Reserve, which sets short-term interest rates and periodically injects “liquidity” into the marketplace to cope with financial crises, and acts as a lender of last resort.

The Fed’s policymaking decisions are made in periodic meetings of its “Open Market Committee.” The committee consists of 12 members – the seven members of the Fed’s Board of Governors; the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York; and four of the other 11 other Reserve Bank presidents.

In other words, the monetary policy of the US – the world’s largest economy – is effectively controlled by 12 people.

According to the Federal Reserve Act, the “monetary policy objective” mission of the Fed is to:

… promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.

So, how well has the Fed accomplished these goals? Let’s focus on the issue of “stable prices.”

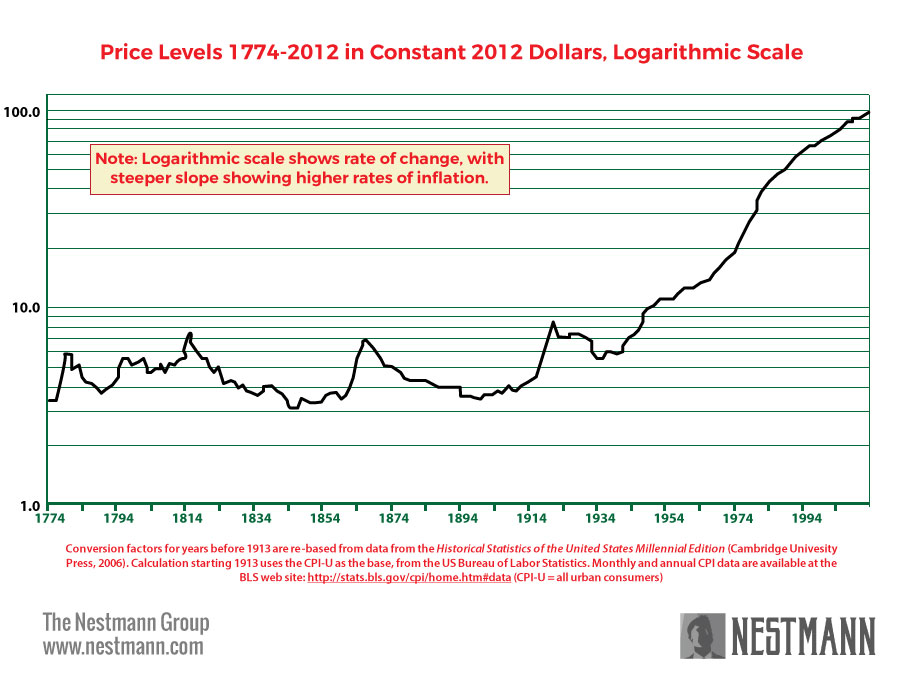

Source: Oregon State University

The graph you’re viewing is a historical record of US price inflation from colonial times to the present day. Note that price levels in the early 20th century, before the Fed came into existence, were roughly the same as they were in colonial times. What mechanism kept prices stable, if not a central bank?

In the first 130-plus years of US history, America operated on a “gold standard.” In other words, the value of a dollar was defined in terms of gold, and anyone who held dollars could exchange those dollars for gold. At times the country used a bimetallic – gold and silver – standard. At the same time, the US dollar wasn’t “legal tender” – if you didn’t want to accept dollars as payment for your goods or services, you didn’t have to. You could demand payment in gold, silver, or even accept payment in private currencies issued by many of the country’s banks.

In other words, there was competition for money. Nor was there a mechanism in place for a lender of last resort to “inject money” into the system, as the Fed’s mandate permits it to do.

As the graph demonstrates, this system worked superbly at controlling inflation. Once a committee of 12 started calling the shots, however, inflation began to rise at almost an exponential rate.

For decades, discussion of a return to the gold standard has been mostly restricted to earnest discussions among libertarians. Occasionally, a professor publishes an article on it in a seldom-read publication. But that’s starting to change, thanks to a statement President Donald Trump made during his campaign. In a March 2016 interview, he said:

“We used to have a very, very solid country because it was based on a gold standard… Bringing back the gold standard would be very hard to do, but boy, would it be wonderful. We’d have a standard on which to base our money."

I don’t know how much President Trump actually knows about the gold standard, but his statement is factually correct. Ending the Fed’s monopoly over money and interest rates would be hard to do, but it could go a long way toward fulfilling his promise to “make America great again.”

But what, exactly, would have to happen for this to occur?

First, Congress would need to abolish the Fed. There’s little political will to do that now, other than a few Tea Party Republicans willing to at least entertain the idea.

That’s just for starters. Congress would also need to redefine the dollar in terms of a unit of gold – establish a price point at which the Treasury would be obligated to exchange gold for dollars. And because a gold standard works well only when all major countries adhere to it, the US would need to persuade its major trading partners – think China, Canada, the EU, and others – to go along with it.

That might not be as hard to accomplish as you think. The dollar is already effectively the world’s reserve currency. Backing it with gold wouldn’t change that status, other than making it more attractive. Many countries also effectively link their own currencies to the dollar, including China and much of Central and South America.

The biggest political obstacle to overcome, though, will be the ingrained belief that in a financial crisis, there must be a lender of last resort. To that, I would simply say, “Why?”

In the financial crisis that began in 2007, numerous banks, financial institutions, insurance companies, and manufacturers were effectively bailed out by the Fed. They carried out risky lending and underwriting practices, knowing that if a crisis occurred, they could expect a handout.

Critics say that in a world with a gold standard, insurance giant AIG would have collapsed. So would nearly all of Wall Street’s mega-banks, most US auto manufacturers, and many other companies. The recession would have quickly turned into a depression, with cataclysmic results for the economy.

But that’s missing the point. In a world with a gold standard, the financial excesses that brought about the events beginning in 2007 would never have occurred. If your business isn’t expecting a handout if and when times get rough, you tend to operate it more prudently.

Perhaps the best argument for a gold standard came from former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, who, paradoxically, opposes it. In testimony before Congress in 2011, he was asked, “Why do people buy gold?”

Bernanke’s reply: "As protection against of what we call tail risks: really, really bad outcomes."

Indeed. I couldn’t have said it better myself.